Redefining Operator and Owner Relationships

Nearly all hotel management agreements define a Force Majeure Event (aka an Extraordinary Event), which may occur either alone or in combination during the life of the contract that is beyond the reasonable control (a “catch-all” phrase commonly used) of the Owner or the Operator. If either party is delayed or prevented, in whole or in part, in complying with any term of the agreement due to a force majeure event, the party is generally excused from such obligations or conditions for a period of time equivalent to the delay caused by such an event. However, the affected party needs to make reasonable efforts to mitigate the consequences of the force majeure event, and often, such excuse of performance excludes, without limitation, obligations of a monetary nature, procuring and maintaining insurance, and/or exercising rights under the agreement. Indisputably, when a force majeure event occurs, the burden of risk is greater on the Owner who typically employs the hotel’s team, needs to meet debt service, and is liable for all costs of doing business, while relying on the Operator to generate sufficient cash flows to meet those requirements.

COVID-19 largely qualifies as a force majeure event facing the industry at this point. Its unprecedented nature has taken all stakeholders by surprise, requiring us to relook the various facets of the hospitality business. Among these, hotel management agreements, defining Owner and Operator relationships, are under scrutiny to ensure that interests of both parties are better protected, going forward. Below, we have highlighted select terms and clauses that need specific attention based on the learnings from this crisis.

- Force Majeure Clause Itself: Contracts differ in defining such events and the treatment of consequences of such events. The Operator is specifically excused for budget deviations, performance test failure, and operating in conformity with brand standards. At times, even the territorial restrictions are not extended on account of a force majeure event. On the other hand, the Owner is required to make all payments (including fees owed to the Operator) and meet project development milestones (with minimal exceptions). There is a possibility that going forward, “pandemics”, “epidemics” or similar words may be more widely used in the detailed description of such events in management contracts, but more importantly, the excuse of performance as well as the termination rights granted (if any) need to be more balanced between the Owner and the Operator. Legal review of this clause is more important than ever before, especially when used as defence by either party, ensuring that neither unduly suffers the consequences of such events.

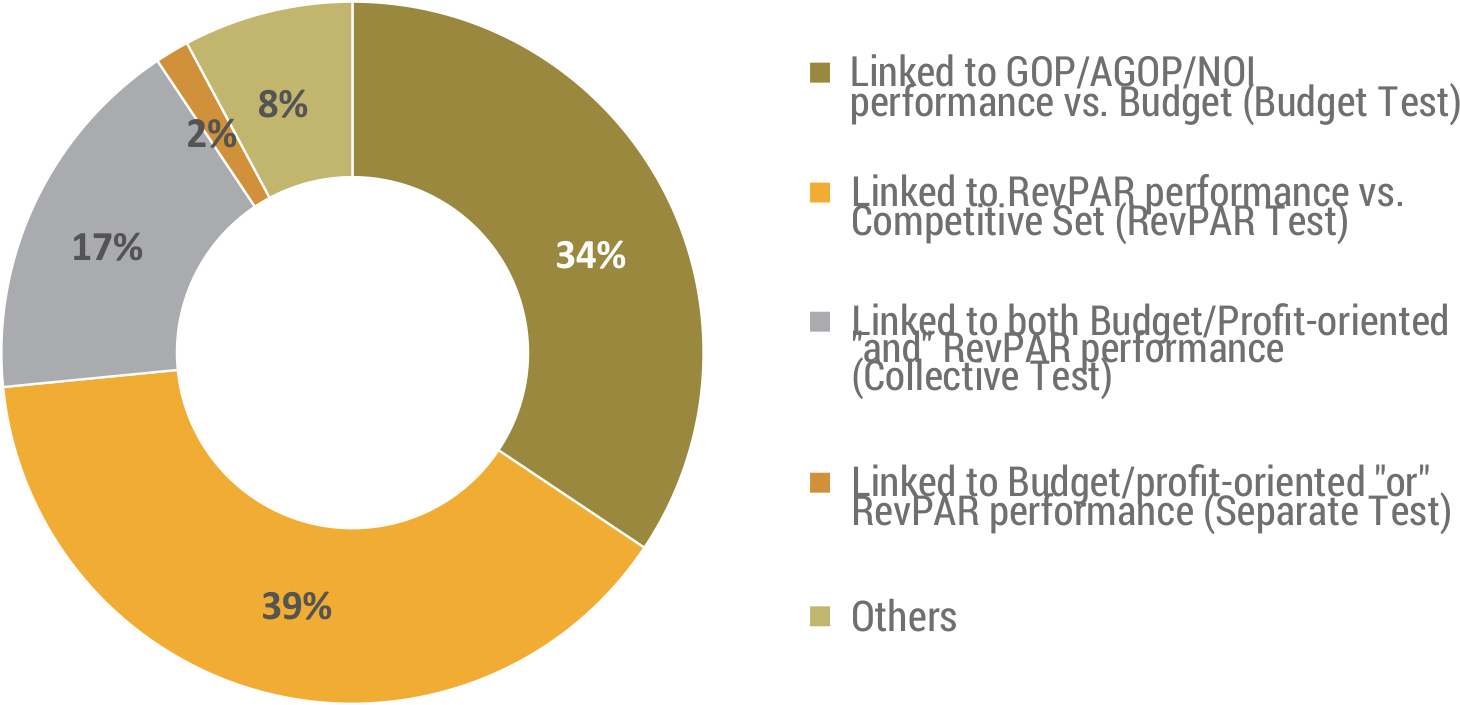

- Operator Performance Test: A single-pronged Budget or RevPAR test is the most popular type of performance test in South Asia. A collective test requires the Operator to fail “both” the Budget and RevPAR tests to give rise to the Owner’s right to terminate the contract, whereas a separate test requires the Operator to fail “either”. Moving forward, Owners should not accept a collective test at all. Also, for a budget test, one must increasingly look at actual NOI instead of actual GOP vs the budgeted figure. Given the high operating leverage of hotels (ratio of fixed costs to variable costs), it is necessary to account for the fixed charges a hotel incurs when testing the operator’s abilities to manage a hotel efficiently – an aspect that has been highlighted by the ongoing crisis.

Figure 1: Type of Operator Performance Test | South Asia

Source: 2020 Hotel Management Contract Survey | South Asia by Hotelivate

Another thing to consider is that while it is fair to shield the Operator from a test failure on account of a force majeure event in case of a budget test, for a RevPAR test it can be argued that since the hotel is being compared to a carefully chosen competitive set in the local market, performing at par with it should be the minimum requirement (all hotels being similarly impacted).

- Shorter Term: The average length of the initial term in South Asia is 20.7 years and for the renewal term it is 8.2 years. For upscale-luxury hotels, the initial term can be as long as 30 to 40 years, averaging around 25 years. Events like COVID-19 make us realize that the industry dynamics cannot be predicted so long out, and thus, the hesitation of Owners to be locked in with a brand for such lengthyperiods is justifiable. This needs to be addressed going forward, possibly with shorter initial terms and multiple renewal terms on mutual consent of both parties and subject to renegotiation.

- Provision for an Owner’s Priority: Presently, less than 10% of the South Asian management contracts provide an owner’s priority return. Here, the incentive fee payable to the Operator is subordinated to the owner’s priority amount and expressed as a percentage of the available cash flow (broadly defined as the amount by which cash flow exceeds owner’s priority). In such instances, the fee ranges between 10%-30% of the available cash flow. Seen as a tool for attributing a more proportionate amount of business risk to the Operator, this incentive fee structure can be extremely rewarding in the good years, while in times like this, the Owner is not obligated to pay the incentive fee unless sufficient cash flows are generated. We believe a greater number of contracts should start incorporating this provision as a learning from this crisis.

- Centralized Services: Group-wide services provided by the Operator tend to cost anywhere between 7.5%-12.5% of Gross Revenue. While most Operators do not share a complete list of all services and their corresponding fees/costs, this needs to be more transparent and equitably allocated between the system’s hotels. Particularly, there needs to a provision to tackle times like this, when the property is unable to directly benefit from these services (either because the hotel has ceased operations or is doing very low volume of business).

- Indemnification: Under an indemnity clause, the indemnified party is legally exempted from any loss or damages that may arise from claim(s) against it. In hotel management agreements, this risk-shifting clause usually favours the Operator, where the Owner indemnifies and keeps indemnified the Operator against all loss or damages arising out of or in any way related to the hotel or performance of the Operator of its duties under the agreement, unless it can be proven that the liability was caused by the Operator’s wilful misconduct or gross negligence. The scope of this clause needs special attention specially to prepare for events like COVID-19, when guests or employees could become ill at the hotel and seek damages, the hotel could miss deadlines to pay vendors or honour other credit agreements etc.

- Condemnation/Taking/Eminent Domain: With governments expropriating private property for public use, such as hotels to house medical professionals or as quarantine facilities during the pandemic, this clause has become expressly significant. At present, the majority of the contracts permit the Operator to unilaterally terminate the agreement if the hotel or a substantial portion of it is condemned, taken or expropriated for an indefinite period of time. The Owner typically does not have any termination rights under this clause. Furthermore, if the Owner receives compensation from the government, it is obligated to pay the Operator a fair and reasonable share of the amount. Going forth, this clause needs to be modified such that the Owner is accorded the same termination rights as the Operator.

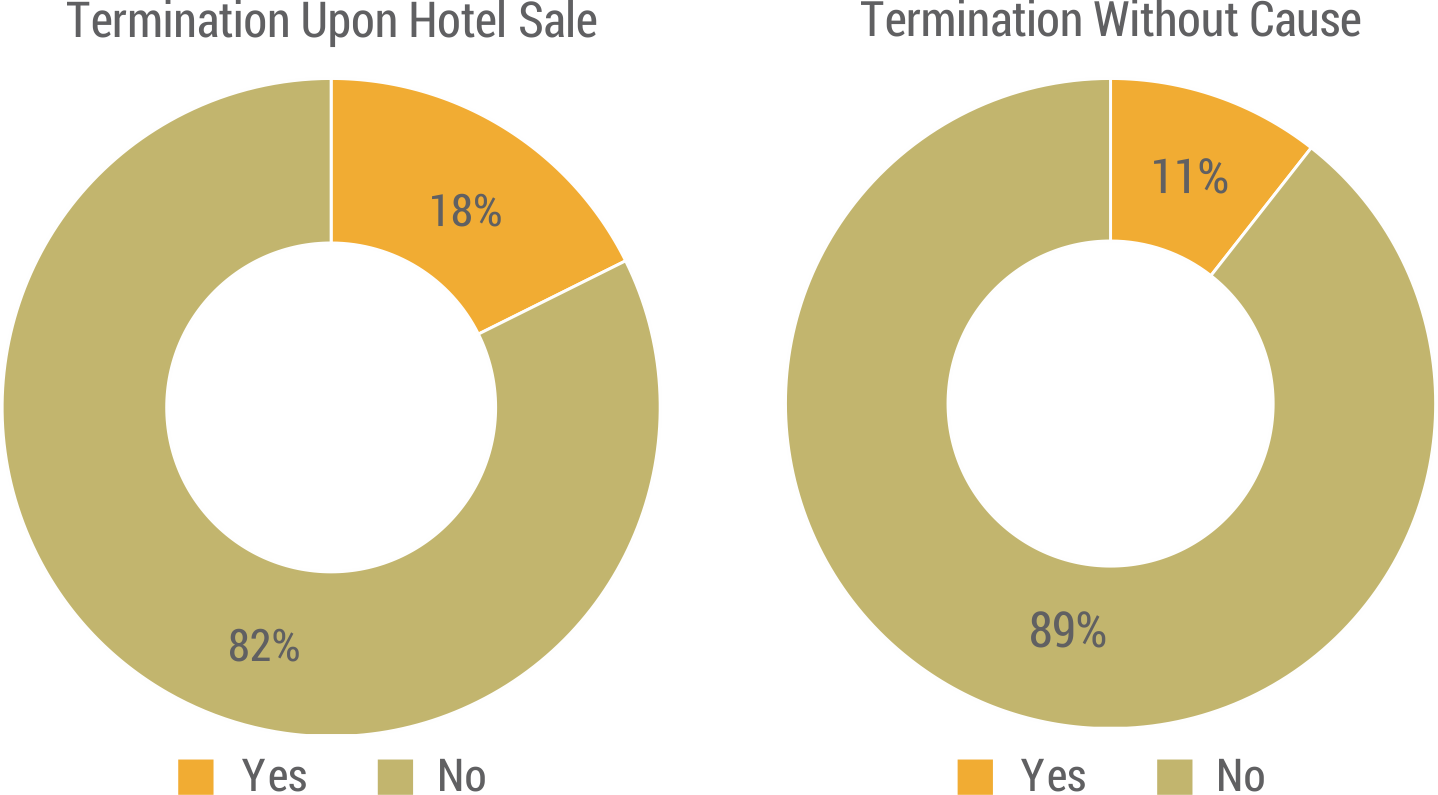

- Termination Rights of the Owner: Currently, only 18% of the hotel management contracts in South Asia allow the Owner to terminate the agreement upon hotel sale, and just 11% accord “at will” termination rights to the Owner. Extraordinary events like COVID-19 that cause significant disruption of business, depletion (or wipe out) of revenues and ultimately, hotel closures, may necessitate hotel Owners to put their properties up for sale. Under such circumstances, being encumbered with a lengthy management contract reduces the buyer universe significantly as well as the sale price. Hence, there is an incentive for Owners to negotiate unilateral termination rights, though it will attract a termination fee payable to the Operator. The key aspect to keep in mind is that the sales premium an Owner expects by selling a hotel unencumbered with a management contract should be higher than the termination fee.

Figure 2: Owner’s Termination Rights | South Asia

Source: 2020 Hotel Management Contract Survey | South Asia by Hotelivate

While the management contract terms that need a relook as we recover from the crisis could far exceed the ones mentioned above, this can serve as a starting point. As negotiations take place and contracts are re-evaluated, many nuances may surface based on individual experiences of the Owners. Also, the manner in which the parties deal with the crisis, and the trust they have in each other coming out of it, will be a major factor in shaping contracts in the years to come.

For more information, please contact Manav Thadani on [email protected] or Juie Mobar on [email protected]